Article originally appeared on the MTV Indies blog on August 26th, 2015.

Hello harmonic people,

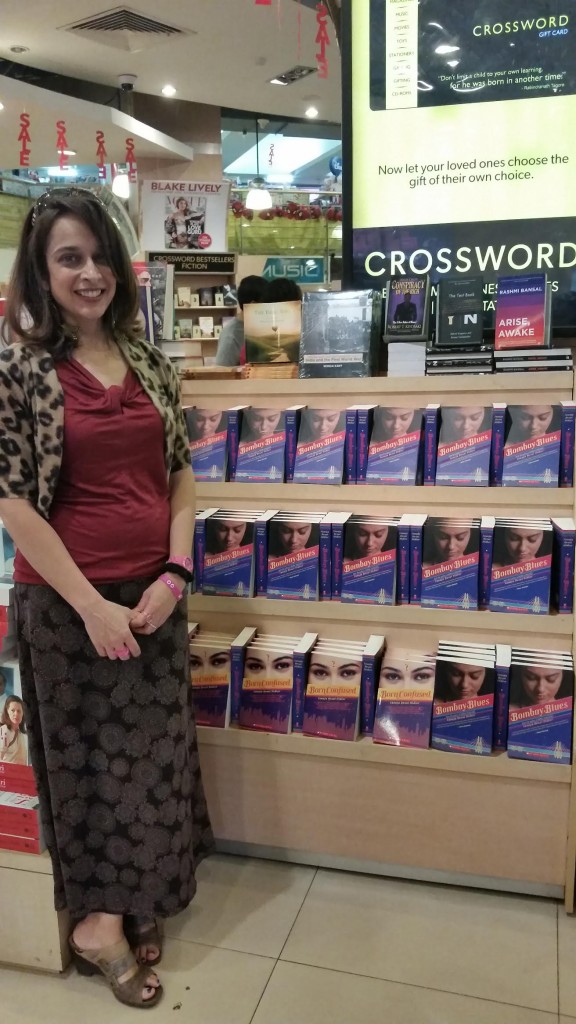

I’m an author/singer-songwriter, Boston-born and now based in London, though Bombay was my primary mental residence —impassioned (pre)occupation —for the last four years. My second book and album are inspired by it: Bombay Blues (the sequel to my first novel, Born Confused) and my accompanying ‘booktrack’ of original songs, Bombay Spleen.

Bombay was a mystery to me (I’d only lived there two years as a Suresh Colony baby)…but a mystery in my blood, a literal motherland: My mother was Vile Parle born and raised; my parents met in med school in Parel; my brother was born near Marine Lines.

I always longed to know this city of family history, as well as forge my own connection to it; this eons-old desire—deepened and amplified by becoming a mother myself–fueled both the book and album.

The album title is a reference to Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen-—his prose-poem to Paris, which my protagonist, Indian-American photographer Dimple Lala is reading when the story opens.

And Bombay Blues/Spleen are kind of my prose-poem to Bombay. My ode to the mother lode. Though they can be read/heard independently, for me they’re one story relayed across multiple media. The prose and songs developed organically side by side; I don’t recall it being a conscious decision so much as a natural way for me to explore and express the story, as books and music have been a big part of my life since I was a child; as an adult (or, older child!) I was the frontwoman in bands in NYC and London, and also made an album of original songs to accompany my first novel, Born Confused two years after that book first released: When We Were Twins (which was featured in Wired Magazine for being the first ever ‘booktrack’, which was lovely).

As well, music is a main theme in both my books: how it brings people together, as a universal language, as well as the way it transforms with culture and chronos —moves its grooves with the diaspora. It’s also what some of my characters actually do/pursue (both novels are populated by fictitious DJs, musicians, producers, nightclubs, live music gigs—and mentions of ‘real’ indie/under-and-over-ground influencers from the music scenes in NYC and London, and of course, India, as well).

The writing process for both Bombay Blues and Bombay Spleen was fully intertwined from inception to fruition: It took me three years to complete both—and they were finished within days of each other, during a very hectic NYC April spent in-studio in Brooklyn with producer Dave Sharma by day, and doing my final book pass for editor David Levithan by night. All along the way, each form helped me to dive deeper into the other — both lighting paths to arrive at the story.

I knew from early on that I wanted Bombay Blues to have the feel of a piece of music (the book is an exploration of the blues on many levels, including the musical sense, too—but the joyful tones too). Likewise, I wanted Bombay Spleen to have the feel of a story—and to not only create an arc that would parallel the heroine’s journey in Bombay Blues, but also one that would trace (not necessarily chronologically) the story of Bombay itself, from its beginnings as seven islands later reclaimed to become the city we know today. Wreckage rock was the term that kept coming into my mind as a guide; the feel of the sea, sunken treasure rising from the ruins, a kind of tidal hello-goodbye.

Bombay Spleen opens with “Catherine”, an ode to Catherine de Braganza, the Infanta of Portugal, whose dowry to Charles II was the islands that became modern-day Bombay. It’s the ‘beginning’ of the story in this sense, a birth of a version of the city (the album bookends this with track “Lady Liberty”). The Spleen songscape includes Bombay settings Chor Bazaar, Juhu Beach, Mount Mary, Colaba, Mahim, Mazagaon, Parel, Old Woman’s Island, Chuim Village, Union Park, Lands End, Worli Fort, Reclamation (and even NYC and London) — and Heptanesia.

Heptanesia. What a word! Too good to be true—though it is true: the earliest documented name for the islands that were Bombay, from the ancient Greek for ‘cluster of seven islands’. When I discovered this term along my researching way, I knew I just had to use it. Such a mysterious term—yet so official sounding, authoritatively evident: like a secret clasped in your own very hand. The word immediately evoked ideas of amnesia, anesthesia, synesthesia. Remembering, forgetting—and the feeling too much that can lead to this—and the thin line, the bridge, really, between truth and fiction.

These are all themes in the “Heptanesia” chapter of Bombay Blues too, both in terms of the protagonist’s dynamic with Bombay as well as in a personal relationship (Heptanesia is also the name of a fictitious music venue in the book, where some major shifts occur for Dimple).

It felt fitting, necessary that a take on this semi-mythical place be a part of my book and album—as the city that Dimple (and I) were seeking is in many ways semi-mythical: a space of memory, history, aspiration, imagination.

But isn’t any place, experience always a mix of these things? Of whatever the dweller brings to the table? And there are at least as many cities in a metropolis as there are inhabitants—far more than that, as one doesn’t have to physically live in a place to inhabit it…or be inhabited, even possessed by it, in a sense (see: the power of nostalgia).

Humans have avatars; so do places. In Bombay Blues, Dimple explores Bombay—the place of a personal past, of family history and mythology that she is seeking her own connection with (which I, on my parallel journey, was doing writing it). But she also explores Mumbai—the modern-day metropolis and perhaps a future one too; Unbombay—a fictitious zone that she unexpectedly discovers when she drops the map (less a place, more a mental space about existing in the present moment); and Heptanesia–the ancient, the before the ‘before’ that goes so far back—nets the past into the future—so it’s full-circle here again.

For me (and Dimple), Heptanesia is a kind of meeting of all these spaces, pasts, presents, futures. Like a chord, a set of notes composed of the various avatars of the city, when played together these strands approximate the sound of one city, but a city with many layers. And it was interesting for me to explore the moments these metropolitan avatars could strike a chord…or not—their harmony, but also the dissonance between, for example, Bombay and Mumbai (or, when your preconceptions/familial history in a place rubs up against your actual experience of it today).

Dimple is a traveler on unknown (however in-the-blood known) terrain; as an Indian-American in India, and perhaps even more so, as the writer and songwriter of a new story I was still figuring out: I was, too. And a traveler’s anonymity, unknownness: It allows you to get to know other layers, potential versions of yourself as well as of a place, people, a situation. You become strange to yourself in a strange land (your known land can shift its own landmarks, too). This can be a real portal. An opportunity for (or even to consider): change.

Inhabiting a song, a story always feels like this opportunity.

I’m fascinated by these avatars of ourselves. I believe reincarnation happens within this lifetime—all at once, even: life viewed from different angles, played at manifold tempos. Mixed; montaged; multiple. Constantly shedding, threading new skins.

Maybe that’s what reincarnation’s about: Reinvention.

And ironically, sometimes we can be most ourself—when we embrace ourselves. All our swimming cities. In all our contradictions—which are no longer so if we widen our frame, deepen our definitions. Throw a light.

Ironically, sometimes we can find our way, or at least a way…when we get a little lost.

Drop the map.

In Bombay Blues, heroine Dimple literally drops the map, loses her way—and in so doing, discovers another layer to the metropolis, goes deeper in. All the way to ‘Heptanesia’. And the parallel journey for me writing her was that I had to let go of a lot of my original plans for what my book and album would be, should be—as soon as I landed in India and began to discover what they could be.

Which is always a more compelling compass: Possibility.

I wrote “Heptanesia” with London/Ghent-based Marie Tueje (I wrote about half of Bombay Spleen with her, the other with NYC’s Atom Fellows). The track was produced by Dave Sharma in Brooklyn and features the lovely legendary Jon Faddis on mute trumpet, and warm wonderful Neel Murgai on sitar. A dream team (along with Gaurav Vaz, who plays bass elsewhere on Bombay Spleen): all fine musicians—and still finer people. I’m lucky to count them as friends. And I think, hope that closeness, that intimacy comes across in the songs.

And no less a part of team Spleen: “Heptanesia” director Tim Cunningham (whom I’d met in an intensive filmmaking course years ago in New York—sweating profusely as we lugged gear around Union Square that summer, we vowed then to make something together one day…and at last it happened!). We met up a few times in SoHo to talk through things. Then in West London to shoot. For the music video, the idea was to go for a torch-singer-with-Bollywood-and-Ingmar Bergman’s Persona-touch look/feel (thank you hair/makeup artist Justine Wade)—an older-era vibe mixed with present-day Bombay footage (converging an old/new city in a time warp, as happens in the song and book). There are some visual references to the Wizard of Oz too (a book theme/chapter is “Home is Not a Place”, another take on ‘there’s no place like home’).

Tim directed, shot, and edited the video here in London. Additional Bombay footage was shot by ace Bombay-based filmmaker Shanker Raman. The video also includes some of the footage I took in Bombay during my research trip while taking visual notes for Bombay Blues (for example, one time crossing the Sea Link Bridge—which is almost like a character, and definitely a muse, in Bombay Blues–I just held my camera up to the window a few seconds to remember the phantom-ship feel of the structure; this shot ended up interspersed through the video).

The video features two little mergirls that make a home for and of me every moment of every moment. And the street sounds are from a videoclip I took during a fishmarket visit with my beloved Suresh Mama (in Pune—shhh!).

I hope you enjoy this love song to Bombay, in all her incarnations.

Xx,

(Hep)Tanuja